The first days after a death can feel like you are living in two worlds at once. In one world, you are grieving—staring at a familiar pair of shoes by the door, listening for a voice that will not come, trying to make sense of a loss that arrived too fast. In the other world, you are suddenly responsible for practical decisions: phone calls, travel plans, priest schedules, family expectations, and questions you never expected to answer so quickly. For many Hindu families, that in-between space is held by what people often call the 13 days mourning Hindu period—the Hindu mourning period that carries the family from the moment of death into a new, steadier rhythm.

It is important to say this early and gently: there is no single “correct” version of these days that fits every family. Rituals after death Hindu traditions vary widely by region, language, community, lineage, and the guidance of a family priest (pandit). Some families describe the period as 10 days, some as 13, some as 16, and some blend customs when relatives come from different backgrounds. The heart of the practice, though, is consistent: to honor the person who died, support the family as it transitions, and offer prayers that help the departed move onward with peace and dignity.

Why families describe the mourning period as “13 days”

When families search phrases like 13 days mourning Hindu or what to expect after Hindu death, they are usually looking for a map. The number “13” often points to a culminating rite commonly associated with bringing the departed into the ancestral lineage, along with a communal meal and prayers that help the family re-enter normal social life. In many North Indian communities, the 13th-day gathering is known by names like terahvin, while other regions have different names and timeframes. What matters most is the purpose: to mark a threshold, and to do so with intention rather than rushing through grief in private.

During this period, families may observe a sense of ritual restraint—simpler clothing, fewer social events, and a more inward daily rhythm. Some of this is spiritual, and some is communal: when your family is mourning, the community knows to come support you with food, presence, and prayer rather than expecting you to host celebrations or maintain normal routines. It is not a punishment. It is a container.

The first day and the first night: what families may do right away

In many Hindu traditions, the practical timeline begins quickly after death. Loved ones may bathe and dress the body, place flowers or sacred items, and prepare for the final rites. Some families recite prayers softly in the home; others move promptly to a funeral home, crematory, or a place of cremation arranged through local services. If relatives are traveling, the family may be balancing spiritual urgency with real-world logistics—airline schedules, time zones, and the need for certain people to arrive.

In many communities, cremation is the customary form of disposition. In the United States, cremation is also increasingly common across all faith backgrounds, which is why so many families—Hindu and non-Hindu alike—find themselves making decisions about ashes, memorialization, and timing. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the U.S. cremation rate was projected to reach 61.9% in 2024, reflecting how frequently families now choose cremation as part of modern end-of-life care. For additional trend context, the Cremation Association of North America also publishes annual industry statistics and projections that many funeral professionals use to understand how family preferences are changing over time.

This matters because the most emotionally charged moment is not always the cremation itself. For many families, it is the quiet day when the cremated remains are returned—often in a temporary container—and the question becomes: what happens next?

Daily life during the Hindu mourning period: prayer, simplicity, and support

In the days following the death, families often describe a shift to a simpler daily structure. Some will hold short prayer gatherings each day. Some will read sacred texts or recite mantras. Some will focus on offering water, light, or food as a symbolic act of care. In many households, the family keeps things calm and understated—less entertainment, fewer outings, and limited participation in weddings, festivals, or parties during the Hindu bereavement customs window.

Dietary practices can also change. Many families choose vegetarian food for the period, avoid alcohol, and keep meals plain. Others follow specific rules based on community tradition—such as avoiding onions and garlic, or eating only once per day for certain days. These choices often exist to support focus and purity during mourning, but they also have a human purpose: when the mind is raw, simpler food can feel grounding.

If you are supporting someone through this period, one of the kindest things you can do is ask what would feel helpful instead of assuming. Some families want company; some want privacy. Some want help coordinating calls and meals; some prefer that non-immediate relatives wait until the final-day gathering. Mourning has rules, but it also has personality.

Shraddha, pind daan, and the meaning families attach to offerings

As families look ahead to the later days, they may hear words like shraddha rites and pind daan. These terms are sometimes explained too technically online, which can make people feel behind or confused when they are already exhausted. One helpful way to understand them is as acts of remembrance and responsibility—rituals that express continued love and duty toward the person who died and the ancestral line they belong to.

In Hindu tradition, shraddha is a ceremony performed in honor of a dead ancestor. As Britannica explains, shraddha is understood as both a social and religious responsibility within many Hindu communities, rooted in the relationship between the living and the ancestors. Families may offer food, water, prayers, and charity. The details vary, but the emotional logic is recognizable: we continue to care, even after death.

Pind daan is often described as an offering—commonly rice balls (pinda) and water—made with prayers for the departed. Families may do this in the home, at a temple, or at a pilgrimage site, depending on tradition and practical realities. For some, this is the moment grief becomes slightly less chaotic, because the family is doing something with their hands, together, with purpose.

What the 10th to 13th day can feel like: a turning point, not an ending

By the second week, many families feel a shift. The earliest shock has softened into a steadier sadness. Relatives who traveled may be preparing to leave. People begin to ask, gently, whether the family is eating, sleeping, and managing daily life. The concluding rites—often associated with the 13th day—can feel like a public acknowledgment that the family has crossed a threshold. The person is still loved. The grief is still real. But life begins to move again.

In some homes, the 13th day includes a gathering where prayers are offered, offerings are made, and a meal is served to relatives, neighbors, or community members. Families who have been observing restrictions may begin to ease them afterward. In others, the concluding day is quieter—especially in diaspora communities where relatives are scattered, priests are booked far in advance, or the family simply needs privacy.

If you are worried about doing things “wrong,” it may help to reframe the question. The deeper goal is not perfection. The goal is sincerity, respect, and care—toward the person who died, the traditions that hold you, and the living family members who are trying to survive the first two weeks.

Why customs vary so widely across communities and regions

Families sometimes feel surprised when relatives disagree about details: which day to do which prayer, whether shaving the head is expected, what foods are allowed, whether the 13th day is essential, or whether the family should travel to a holy place. These differences are common—and they do not mean anyone is disrespecting the deceased. They usually reflect regional practice and family lineage.

If you need a simple way to talk through differences without escalating conflict, it can help to separate “purpose” from “method.” Most relatives share the same purpose—honor the departed and support the family. The methods can differ:

- Timing: some families complete key rites within 10 days; others focus on the 13th day as the main communal threshold.

- Ritual roles: who leads prayers or performs offerings can depend on family structure, community norms, and priest guidance.

- Household rules: dietary and social restrictions often vary by region and by the family’s own comfort.

When possible, families find peace by choosing a path that respects tradition while also respecting the realities of modern life—work schedules, elder health, travel constraints, and the emotional limits of people who are grieving.

Where cremation ashes fit into the first two weeks

In many Hindu communities, cremation is followed—sometimes soon, sometimes later—by the immersion of ashes in a sacred body of water. Other families choose to keep ashes temporarily while coordinating travel, priest availability, or a gathering when relatives can be present. This is where practical planning can quietly reduce stress. If ashes will be kept at home for any length of time, families often want a container that feels secure and respectful rather than improvised.

If you are exploring what to do with ashes, it can help to remember that “next steps” do not have to happen immediately. Many families keep ashes at home for weeks or months while they decide on a ceremony that fits their beliefs, budget, and family needs. Funeral.com’s guide on what to do with ashes walks through common options in plain language, including scattering, burial, and creating a home memorial.

For families considering keeping ashes at home, the questions are often both practical and emotional: Where should the urn be placed? Is it safe with children or pets? How do we handle visitors who may not understand? Funeral.com’s resource on keeping ashes at home offers guidance on safety, placement, and household comfort—helpful whether you plan to keep the ashes long-term or only until a ceremony can be arranged.

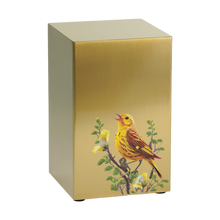

Choosing an urn without turning it into a second burden

Some families worry that selecting a memorial container is too “material” during a sacred mourning period. Others find the opposite: choosing something beautiful and lasting feels like a form of care. If you are navigating this decision, it may help to think of an urn as a practical vessel that supports your plan—whether that plan is a home memorial, a future immersion ceremony, or sharing ashes across relatives who live far apart.

Funeral.com’s collection of cremation urns includes a wide range of styles and materials, which can be helpful if your family is balancing tradition with modern living spaces. If your plan involves dividing ashes among siblings or keeping only a portion at home, small cremation urns and keepsake urns can make that shared approach feel orderly and respectful rather than improvisational.

Many families choose one primary urn and then add keepsakes for adult children, siblings, or elders who want a small, private way to grieve. Funeral.com’s Journal guide Keepsake Urns Explained offers a calm walkthrough of how keepsakes fit into real family dynamics—especially when people have different timelines for letting go.

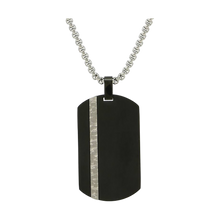

Cremation jewelry as a modern extension of an ancient impulse

In many Hindu families, devotion is expressed through tangible acts—lighting a lamp, offering water, preparing food, visiting a temple. In a modern diaspora context, cremation jewelry can sometimes serve a parallel emotional function: a small, wearable reminder that makes love portable. It does not replace prayer or ritual. It simply supports the human truth that grief travels with you.

If your family is considering cremation necklaces or other memorial pieces, Funeral.com offers a curated selection of cremation jewelry as well as a focused collection of cremation necklaces. If you want a practical primer before choosing, Funeral.com’s guide Best Cremation Necklaces for Ashes explains materials, seals, and what “capacity” means when the container is small.

For families observing the Hindu funeral timeline and related rites, cremation jewelry may be most helpful when relatives live far away or when the ashes will eventually be immersed but loved ones want a small portion to remain close. These choices can coexist with tradition when approached thoughtfully and with family agreement.

When water burial enters the conversation

Families sometimes use the phrase water burial to describe several different things: immersing ashes in a sacred river, scattering ashes over ocean waters, or placing ashes in a biodegradable urn designed to dissolve. If your ceremony is happening in the ocean, it is also wise to understand the legal framework that governs burial at sea in U.S. waters. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains burial-at-sea guidance under its general permit, and the federal regulation at 40 CFR 229.1 includes requirements such as the three-nautical-mile distance from shore for ocean burials.

If you are trying to visualize what that distance actually means in real planning—especially when coordinating a charter or trying to avoid a stressful last-minute change—Funeral.com’s guide Water Burial and Burial at Sea: What “3 Nautical Miles” Means translates the rule into practical terms. For families choosing a dissolving container for ocean release, Funeral.com’s resource on biodegradable water urns explains how different designs float, sink, and dissolve.

Funeral planning during grief: gentle structure can be a form of care

Even in families with strong traditions, grief can create decision fatigue. That is where funeral planning can be compassionate rather than clinical. Planning does not mean rushing the sacred parts. It means reducing avoidable stress—understanding timelines, confirming who needs to be present, choosing containers that match your plan, and talking about costs without shame.

Cost questions are especially common when families are balancing travel, time off work, and religious services. If you are searching how much does cremation cost, Funeral.com’s guide How Much Does Cremation Cost in the U.S.? walks through common price structures, typical add-ons, and ways families keep expenses manageable without losing dignity. For urn decisions specifically, Funeral.com’s practical article How to Choose a Cremation Urn can help you make choices that fit both tradition and the realities of a home, a temple, or a future ceremony.

Holding tradition and flexibility at the same time

If you are in the middle of the Hindu mourning period right now, you may be tempted to treat these days like a checklist. But many families experience them more like a slow procession from shock into acceptance—a series of mornings where the house feels quieter, a series of evenings where someone remembers a story and laughs through tears, a series of small rituals that say: love continues, even here.

Some families feel comforted by strict rules. Others need flexibility because the world around them has changed—interfaith marriages, immigration, blended households, distance from temples, and work obligations that do not pause for grief. None of this makes the mourning less sincere. It simply means your family may need to translate old wisdom into the language of your present life.

If the days feel heavy, consider choosing one small anchor each day: a short prayer, a candle, a shared meal, a few minutes of silence, or a phone call to an elder who can tell you what was done in earlier generations. These practices do not erase grief, but they can soften the feeling that you are alone inside it.

After the thirteenth day: what continues, and what changes

For many families, the concluding rites do not end love or remembrance. They simply change the shape of it. Annual observances, temple visits, acts of charity, and family gatherings may become the places where remembrance lives. Over time, grief often becomes less sharp and more integrated—a quiet presence rather than a daily emergency.

And if you find that it does not soften, or that daily functioning becomes difficult, it is also okay to seek support. Grief is not only a spiritual experience; it is a human one. The strongest families are not the ones who never struggle. They are the ones who notice struggle and respond with care.

In the end, the first two weeks are not about proving devotion. They are about being held—by tradition, by community, and by the simple truth that love deserves a dignified goodbye. Whether your family’s journey includes cremation urns for ashes, a sacred immersion, keepsake urns shared among siblings, or cremation jewelry carried close to the heart, the goal remains the same: to honor the person who died, and to help the living keep going.