In many households across the Middle East and neighboring regions, grief doesn’t arrive alone. It arrives with footsteps at the door, with neighbors who come even when they don’t know what to say, with relatives who travel across cities and borders, and with the quiet question that hangs in the air after the first embraces: “Have you eaten?” In the middle of sorrow, food can feel like the only language left that doesn’t ask anything back. And sometimes that language is sweet.

For some families, that sweetness takes the form of halva mourning tradition—a simple, nourishing confection served during condolence visits and mourning gatherings. The details change from place to place. In Turkey it may be a warm, spoonable flour or semolina helva made after burial and offered to visitors, a practice described in reflections on “helva of the dead” and mourning hospitality in Turkish culture by SBS Food. In Iranian and Persian-influenced contexts, a fragrant saffron-and-rosewater halva can appear at funerals and remembrance gatherings, noted in family stories and ritual context by the Jewish Food Society. In other communities, “halva” may mean sesame halva (tahini-based), cut into neat pieces and offered with tea as part of funeral hospitality Middle East—an act of care for visitors and a way to keep the grieving household from carrying everything alone.

This guide is here for the person who is grieving and trying to understand what the food means, and also for the person who has been invited into someone else’s mourning space and wants to show respect. If you’ve been searching for Middle Eastern funeral food, condolence visit food customs, or even the blunt phrase halva for the dead, you’re likely trying to do something tender: get it right, without making it awkward.

A sweet that carries more than flavor

Halva is not one single recipe. It’s a family of sweets found across a wide geography, shaped by trade routes, empires, religions, and the quiet persistence of home kitchens. That’s why, when people talk about sesame halva meaning, they might be thinking of a dense, sliceable halva made from tahini and sugar—nutty, slightly bitter-sweet, often studded with pistachios. Meanwhile, someone else might picture a warm halva made by toasting flour or semolina in butter or oil until it turns deeply aromatic, then pouring in sweet syrup. Both are “halva,” but they behave differently on the table and in memory.

In mourning settings, those differences matter because they match different needs. A soft halva that can be eaten with a spoon is easy to serve in a crowded home when people come in waves. A firm sesame halva can be portioned quickly, offered with tea, and sent home with visitors. Across these variations, the consistent thread is not culinary perfection. It’s nourishment: calories for bodies that are tired, and sweetness for hearts that feel like they’ve been scraped raw.

If you’re looking for a helpful way to think about it, consider halva in mourning less as “dessert” and more as a culturally familiar form of comfort food—part of bereavement sweets tradition and grief rituals food that keeps a household functioning when normal life has stopped.

Why sweets appear in grief

When someone dies, visitors arrive carrying condolences, prayers, memories, and sometimes their own shock. The grieving family is hosting without choosing to host. In many cultures, hospitality is not optional; it’s a moral and social practice that signals dignity, community belonging, and care for the living. Offering halva can be a way to fulfill that hospitality in a simple, grounded form—something that can be made in large quantity, served without ceremony, and accepted without creating extra work.

Sweets also carry symbolic weight. They can gesture toward hope without forcing optimism. They can say, “Life still contains softness,” without denying that life also contains loss. And practically, sugar and fat are fast energy. When grief empties appetite, small bites can be easier than a full meal.

In some Muslim-majority contexts, the ethics of feeding others in times of difficulty can be framed as generosity and communal support, with an emphasis on sincerity rather than extravagance—an idea discussed in cultural explanations of halva’s role in mourning shared by Halalification. Even when families don’t articulate the theology, they often live the values: people show up, they sit, they pray or speak quietly, and they eat what is offered because refusing can feel like refusing the relationship itself.

That’s why food customs in mourning are rarely about appetite alone. They are about belonging. They are part of cultural etiquette mourning—a set of gentle rules that help everyone move through a hard day without having to invent the script from scratch.

When halva is served

The most honest answer is: when the community expects it, and when the household can manage it. In many places, mourning has a rhythm—specific days when people gather, visit, or mark the passage of time. In Türkiye, for example, helva and other “soul food” sweets are commonly made after a funeral and also on later remembrance days such as the seventh or fortieth day, as described by Hürriyet Daily News. Some families also observe set remembrance days; one home-cooking account notes helva may be repeated on later mourning days, including the seventh and fortieth day, and on the first anniversary, though practices vary by family and region (Rose Cuisine).

In Iranian contexts, halva is widely associated with funerals and religious gatherings, often scented with saffron and rosewater and served with tea. A Persian cooking source describing cultural practice notes halva is commonly served at funerals in Iran (PersianGood), and the Jewish Food Society similarly frames Iranian halva as present at major life moments, including funerals, in a family tradition.

Across the Levant, Egypt, and other surrounding regions, the offering may not always be “halva” by name, and it may not always be homemade. But the pattern—visitors, tea, something sweet—often repeats. That repetition is the point. In early grief, consistency can feel like a handrail.

If you’re attending a mourning visit and you’re unsure what to expect, it may help to know that there is rarely one “right” version of the ritual. Some homes keep it simple—tea and a few sweets. Some organize larger condolence receptions. Some families are too overwhelmed to host at all, and community members step in. This is one reason Funeral.com encourages families and friends to think in terms of reducing burden rather than following perfect rules. If you want a wider lens on how traditions—food included—change across regions and generations, Funeral.com’s Cultural Differences in Grieving and Funerals offers a helpful starting point.

What it means when food is offered at a condolence visit

In many condolence visit food customs, the food is not a performance for guests. It’s an exchange: “We are here with you,” answered by, “You are welcome in our sorrow.” Accepting what is offered—within your dietary needs and comfort—is often interpreted as acceptance of that relationship. Taking a small portion can be enough. You do not need to praise the recipe. You do not need to make the moment cheerful. You only need to receive it with gratitude and restraint.

If you are worried about saying the wrong thing, let the food carry some of the weight. Simple words are usually best: “Thank you,” “May their memory be a blessing,” “I’m sorry for your loss,” or a culturally appropriate condolence in the family’s language if you know it. Funeral.com’s guide on how to offer condolences can help you keep your message supportive without adding pressure.

And if you’re the one hosting visitors after a death—whether in a Middle Eastern tradition or simply in the universal chaos of grief—please know this: you do not have to do everything. Food traditions are meant to support you, not drain you. If halva is part of your family’s mourning practice and you can manage it, it may feel comforting to follow the familiar steps. If you cannot manage it, it is still okay to accept help.

Many families today lean on community meals, meal trains, and drop-offs rather than preparing everything themselves. Funeral.com’s Sympathy Meals After a Death and Remembering With Food are thoughtful reads if you are trying to balance tradition with real-life capacity.

Respectful etiquette when halva is part of the gathering

Most etiquette problems happen when visitors accidentally make the moment about themselves—over-talking, over-questioning, or trying to “fix” grief with optimism. Food can tempt people into normal-party behavior. Mourning is not a party, even when the table is set. If you want a simple compass for cultural etiquette mourning in homes where halva is served, these principles tend to travel well:

- Accept a small portion if you can, or decline gently without explanation if you cannot.

- Keep your visit short unless the family clearly asks you to stay.

- Follow the tone of the room—quiet if it’s quiet, conversational if others are speaking softly.

- Avoid photographing food, the home, or the gathering unless explicitly invited.

- If you want to help, offer something specific and easy to accept: “I can bring tea tomorrow,” or “I can handle a grocery run.”

If the gathering is part of a wake, visitation, or formal receiving line, you may appreciate Funeral.com’s practical guidance on wake, viewing, and visitation etiquette, including what to wear and how long to stay. These details can feel small, but small details are often what make a grieving family feel held rather than watched.

Where tradition meets modern funeral planning

Many families who carry halva traditions are also living in places where funeral customs look different from what their grandparents knew. Some families hold condolence gatherings at home. Others reserve a hall. Some choose burial; others choose cremation because of cost, distance, or personal preference. In the United States, cremation has become the majority choice in recent years. The National Funeral Directors Association reports a projected U.S. cremation rate of 63.4% for 2025, and the Cremation Association of North America lists a 2024 U.S. cremation rate of 61.8% with continued growth projected.

What does that have to do with halva? More than you might think. When families are navigating funeral planning across cultures, they often discover that “disposition” and “ritual” can be separate decisions. You can honor a family’s spiritual and cultural rhythms—visiting, praying, sharing food, serving halva—while also choosing the practical path that fits your life. Food traditions are portable. They can move with you, even when cemeteries, timelines, and paperwork change.

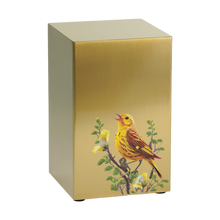

For families choosing cremation, questions often arrive quickly: what to do with ashes, whether keeping ashes at home is okay, and how to choose a container that matches the plan. Funeral.com has several clear, non-salesy resources that can help families make those decisions without rush, including Keeping Ashes at Home, What to Do With a Loved One’s Ashes, and How Much Does Cremation Cost.

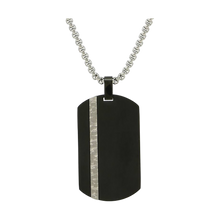

If you’re at the stage of choosing a memorial, browsing options can be less overwhelming when you start with the category that matches your real plan. A full-size memorial might lead you to cremation urns and cremation urns for ashes. If multiple relatives want a personal share, small cremation urns and keepsake urns can support that kind of family structure without anyone feeling left out. If grief feels like it follows you into ordinary errands and workdays, some people choose cremation jewelry or cremation necklaces as a discreet way to carry connection into everyday life.

And because pets are family in many homes, it’s worth saying clearly: pet loss often needs ritual too. Families who keep a condolence table, light a candle, or serve a familiar sweet after loss may find comfort in choosing a memorial for an animal companion as well. Funeral.com’s pet urns, including pet urns for ashes and pet cremation urns, can be explored alongside keepsake options like pet keepsake cremation urns and artistic styles such as pet figurine cremation urns, with guidance available in Funeral.com’s Pet Urns 101.

Even families planning a water ceremony—sometimes called water burial or burial at sea—often keep food rituals close to home, before or after the ceremony, as a way to gather the living. If you’re considering that kind of farewell, Funeral.com’s guide to ocean and water burial urns can help you understand how the urn behaves and what practical rules may apply.

Holding comfort without turning grief into a performance

Sometimes people worry that food at mourning gatherings is “wrong,” or that sweetness makes sorrow less serious. In reality, sweetness is often how communities stay human in the face of death. Halva doesn’t erase grief. It gives the body something to hold onto while the heart tries to catch up.

If halva is part of your family’s tradition, you might find comfort in keeping it simple: make what your elders made, serve it with tea, let visitors come and go. If halva is not part of your tradition but you are visiting a home where it is served, your job is not to interpret it perfectly. Your job is to show up with respect, accept what is offered if you can, and let the family lead.

And if you are building a new tradition—because you live far from home, because you are part of a multicultural family, or because your loved one’s life crossed many worlds—you can still borrow the deeper meaning: nourish the living. Offer something warm. Create a small moment of steadiness in a day that feels unsteady.

In the end, Middle Eastern funeral food is not about food alone. It’s about community refusing to leave someone alone with their sorrow. Sometimes that refusal looks like a chair pulled close. Sometimes it looks like a quiet plate offered without words. And sometimes it looks like halva—sweet, modest, familiar—reminding everyone in the room that comfort can be shared, even when grief cannot be solved.