In the first days after a death, time becomes strange. A family can move through paperwork, phone calls, and meals brought by friends, yet still feel as if nothing has truly “moved.” In many Buddhist communities, that feeling has a spiritual shape: the weeks after death are not only grief-filled, but transitional. The period is often described as an in-between time—an interval when the deceased is no longer living in the ordinary sense, but has not yet fully reached the next stage of existence. For families searching for 49 days after death Buddhism, the question is rarely academic. It is usually a practical, aching one: “What do we do now, and how do we do it respectfully?”

Across Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and other Buddhist traditions, the phrase “49 days” appears again and again. The details vary by lineage and culture, but the shared intention is steady: to surround the deceased with compassion, prayer, and merit, and to give the living a structure for love when love has nowhere obvious to go. And because many modern Buddhist funerals—especially in North America—include cremation, the 49-day period also becomes a time when families are making choices about ashes, urns, and memorial planning alongside the rituals themselves.

Why 49 Days Matters: The Buddhist “Intermediate State”

The idea behind the 49-day period is often introduced in English as the Buddhist intermediate state. In Tibetan Buddhism, this is closely associated with the concept of bardo 49 days—a transitional process between death and rebirth. Encyclopaedia Britannica describes this Vajrayana framework as involving an intermediate period between death and rebirth that lasts 49 days. During this time, prayers and guidance are traditionally offered with the hope that the deceased recognizes the nature of reality clearly and moves toward a favorable rebirth or liberation.

It’s important to say gently and clearly: Buddhism is not one single rulebook. Even within Tibetan lineages, families may practice the 49 days with different levels of ritual intensity depending on their teachers, temples, and personal devotion. In Chinese Buddhist communities, the “seven sevens” structure—weekly observances over seven weeks—often becomes the most visible rhythm. In Japanese Buddhism, memorial observances commonly include key milestones like the 7th and 49th days, with temples guiding families through what is customary in their community. And in some traditions—especially certain forms of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism—families may interpret the after-death journey differently, emphasizing immediate rebirth in a Pure Land through devotion, even while still keeping the memorial schedule for the living. In other words, the number “49” can hold doctrinal meaning, cultural meaning, and emotional meaning all at once.

For many families, the 49 days provides something else that grief often takes away: a sense of steadiness. The Buddhist mourning period is not simply “waiting.” It is active care—care offered through chanting, offerings, generosity, and remembrance, and care received through community support and a calendar that says, “You are not supposed to be done grieving in a week.”

What Families Often Do During the Seven-Week Memorial Cycle

When people talk about weekly memorials, they are usually referring to a pattern of observances every seven days, culminating around the 49th day. In many Japanese Buddhist communities, a 7th-day memorial and a 49th-day memorial are especially common reference points, even when modern schedules mean families combine or adjust dates. A temple schedule shared by the BCO Buddhist Church of Oakland outlines this rhythm clearly, listing family memorial services that include the first seventh day and the forty-ninth day, along with later milestones such as the 100th day and annual observances. A handout from the Fresno Buddhist Temple similarly describes memorial services observed every seven days through the 49th day.

What happens inside these memorials depends on the tradition and the setting. Sometimes the family gathers at a temple with a minister or monks. Sometimes a small ritual happens at home, especially when relatives live far away or when grief makes public gatherings feel too heavy. Often it’s both: a temple service for key days, and a home practice that continues quietly in the background.

In everyday family language, the 49-day rhythm often looks like a few steady, repeating gestures. A simple remembrance space may be set up at home—often with a photo, candles or lamps, incense, and offerings. Families may chant or recite sutras, mantras, or the name of a Buddha (depending on tradition) as an act of prayers for the dead Buddhism. Offerings of food, flowers, light, or incense—sometimes described as ancestor offerings Buddhism—can become a daily or weekly way to express care and gratitude. Many families also make acts of generosity or service in the deceased’s name, holding the intention of “transferring merit.” And then there are the weekly gatherings themselves, whether held every seven days or combined when travel and work make weekly observances impossible, building toward memorial services 7th day 49th day.

Even when the family’s practice is simple, the emotional purpose is profound. The ritual gives grief a place to go. It allows a person to be remembered repeatedly, not only in one intense ceremony, but in smaller, steadier moments. Many families find that this cadence softens the shock of “after.”

How Customs Vary Across Tibetan, Chinese, Japanese, and Other Communities

In Tibetan Buddhist contexts, the language of bardo tends to be more explicit. Families may request teachings, readings, or prayers intended to support the deceased through the intermediate process described in classic texts associated with the Bardo Thodol. If you are navigating Buddhist funeral traditions in a Tibetan lineage, your temple may encourage specific practices—such as recitations, offerings of light, and dedicated ceremonies—especially during the early days and key weekly milestones.

In many Chinese Buddhist communities, the “seven sevens” pattern is often paired with temple rites, home offerings, and communal meals. Families may focus on chanting, incense offerings, and the intention to support the deceased’s peaceful transition. Sometimes elements of local culture blend into the period as well, especially in diaspora communities—meaning the family may be holding both “Buddhist” and “cultural” practices at once, even if they don’t label them separately.

Japanese Buddhist memorial life is famously structured. The funeral may be followed by memorial services that mark the first seventh day, the 49th day, and later milestones like the 100th day and annual observances—patterns reflected in temple resources such as those shared by the BCO Buddhist Church of Oakland and the Fresno Buddhist Temple. In many families, the 49th day is also when ashes are placed in their longer-term resting place—such as a family grave or a temple columbarium—because the memorial milestone carries a sense of spiritual “arrival,” even if grief is still very present.

Other Buddhist traditions may not emphasize a 49-day intermediate state in the same way. Theravada communities, for example, can focus more on merit-making, chanting, and communal support without framing the weeks after death as a fixed 49-day bardo journey. What remains consistent across many communities, though, is the emphasis on compassion, non-harm, and caring action—values that can shape both spiritual ritual and practical decisions.

When Cremation Is Part of the Picture: Ashes, Urns, and Home Practice

Because cremation is increasingly common in the United States, many Buddhist families today find themselves holding ashes during the very same weeks they are holding weekly memorials. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the U.S. cremation rate is projected to reach 63.4% in 2025. The Cremation Association of North America also publishes annual statistics and trend reporting based on state and provincial data. For families, this shift means a very specific reality: the memorial plan often extends beyond the funeral day, and the “where will the ashes go?” question becomes part of the grieving process.

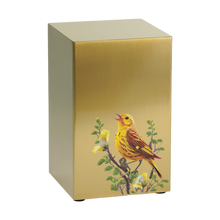

In Buddhist homes, keeping ashes at home for a period of prayer can feel deeply natural—especially during the 49 days. Some families keep the cremated remains on a home altar or remembrance table, then move the ashes to a temple columbarium or family grave after the 49th-day service. If you’re navigating this practically and want guidance that’s calm and concrete, Funeral.com’s resource on keeping ashes at home can help you think through placement, visitors, children, pets, and respectful handling.

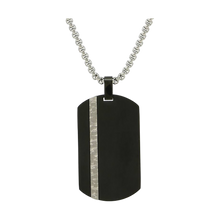

Choosing an urn during this time is not about “shopping.” It’s about matching a container to a plan. If the ashes will remain at home long-term, families often look for secure, durable cremation urns designed for display. If the plan involves sharing a small portion with relatives—especially in large families or across countries—small cremation urns or keepsake urns can make the sharing feel orderly and respectful rather than improvised. If a family member needs something portable, discreet, and close to the body during the hardest weeks, cremation jewelry—including cremation necklaces—can become a gentle bridge between ritual time and everyday life.

Some families like to begin with a broad view, simply to understand what exists. Funeral.com’s cremation urns for ashes collection can help you compare full-size memorial containers across materials and styles, while small cremation urns are often a better fit when space is limited or when only a portion will be kept. If the goal is to share remembrance among relatives, keepsake urns can make that sharing feel intentional and dignified. And for families who want remembrance close to the body, the cremation jewelry collection—and specifically cremation necklaces—offers options that many people find comforting during the earliest weeks of grief.

If your family is also grieving an animal companion—a loss that can feel every bit as life-shifting—Buddhist families often bring the same spirit of compassion and ritual care to pets. Funeral.com’s collection of pet urns and pet urns for ashes includes many forms of pet cremation urns, including keepsake-sized options that fit naturally into a home remembrance space.

Funeral Planning During the 49 Days: Making Room for Meaning and Logistics

One quiet challenge families run into is that funeral planning is not always finished when the cremation is complete. The 49-day practice can include multiple gatherings, temple coordination, and a longer timeline for deciding what to do with ashes. That means planning becomes layered: there may be an initial funeral or cremation service, a series of weekly memorials, and then a 49th-day ceremony that feels like a spiritual threshold.

At the same time, modern families are often working inside practical constraints. Relatives may live in different states. Someone may need to travel for the 49th day rather than the funeral. A temple might have limited service dates. Even if a family’s heart wants a weekly gathering, life may only allow two or three key days. Buddhist communities are usually familiar with this reality, and many temples will help families choose meaningful observances that fit what is possible.

Cost is another reason families may adjust. If you’re trying to understand how much does cremation cost, and how memorial choices (like urns or a temple columbarium niche) fit into the overall budget, Funeral.com’s guide on how much does cremation cost can help you see the real-world pricing layers that change totals—direct cremation vs. services, common fees, and ways families save without losing dignity.

The goal is not perfection. The goal is alignment—choosing a plan that honors your person, respects your tradition, and doesn’t leave the living emotionally or financially overwhelmed. In Buddhist terms, grief is already heavy. Planning should not add unnecessary suffering.

After the 49th Day: What Comes Next and What to Do With Ashes

For many families, the 49th day holds a sense of closure—not because love ends, but because the ritual cycle offers a moment to release some of the fear that the deceased is “stuck” or alone. In Japanese Buddhist communities, later memorial milestones may continue—such as the 100th day and annual observances—again reflected in temple schedules like the BCO Buddhist Church of Oakland listing. The ongoing rhythm matters because it gently reminds the living that remembrance is not an emergency. It is a relationship that changes shape over time.

Practically, after the 49 days, families often make a clearer decision about what to do with ashes. Some keep the urn at home long-term. Some place the urn in a temple columbarium or cemetery niche. Some divide ashes into keepsakes for siblings and scatter or bury the remainder. Some choose a ceremony with water, especially when the deceased loved the ocean or when release feels symbolically appropriate. If your family is considering water burial or burial at sea, Funeral.com’s guide on water burial can help you understand what “three nautical miles” means in real planning terms and how families structure the moment.

And if you’re balancing faith and practicality—especially in mixed-faith or multicultural families—Funeral.com’s article on which religions prefer cremation can help you name what is “traditional,” what is “customary,” and what is simply “what our family can do right now,” without turning the conversation into conflict.

When You’re Not Sure How to “Do It Right”

Families often worry they will offend a tradition, disappoint elders, or fail the person who died. In truth, the heart of Buddhist practice is not performance. It is intention—compassion, respect, and the wish to reduce suffering. If you are unsure, begin by asking a local temple or a trusted practitioner what is customary in your community. Then ask yourself what your family can actually sustain. Weekly memorials do not have to be elaborate to be sincere. A single candle, a short chant, a moment of bowing, a meal shared in remembrance—these can be powerful grief rituals Buddhism when they are done with care.

The 49 days can feel like a bridge: between shock and reality, between presence and absence, between “we just survived the funeral” and “now we have to keep living.” In Buddhism, bridges matter. They are where transformation happens. If your family can let this period be what it is—tender, imperfect, structured, compassionate—then you are already honoring the tradition in the most meaningful way.