In a medical emergency, families often discover something they did not know they needed: a shared language for decisions. The ambulance arrives, the room fills with people and questions, and suddenly everyone is trying to answer the same impossible thing at once. What would they want? What does “do everything” actually mean? What does “comfort” mean in this moment?

That is where planning tools like advance directives, DNR orders, and POLST exist—not to make death easier, but to make urgent moments less chaotic. The problem is that these documents are often talked about as if they’re interchangeable. They are not. Each one plays a different role, and understanding the difference is one of the simplest ways to protect your loved one’s wishes during a crisis.

This guide explains what each document does, how they work together, and how families can prepare in a practical, calm way. It is educational and not legal or medical advice. Requirements vary by state and by care setting, so your clinician and care team are the best source for what applies to your situation.

Start Here: The One-Sentence Difference

If you remember only one thing, let it be this: an advance directive is a legal document that expresses wishes and names a decision-maker, while a DNR and a POLST are medical orders intended to guide treatment in urgent or emergency situations.

The National Institute on Aging explains that advance directives are legal documents that provide instructions for medical care and generally take effect only if a person cannot communicate. A DNR order, by contrast, is a medical order written by a clinician instructing providers not to perform CPR if breathing or heartbeat stops. A POLST form communicates treatment wishes as medical orders during a medical emergency and is typically intended for people who are seriously ill or frail.

Advance Directives: The Foundation for Decision-Making

Think of advance care planning as the process, and the advance directive as the paperwork that results from it. The document is valuable because it does two critical things: it captures your preferences for care, and it names the person who can speak for you if you can’t.

According to the National Institute on Aging, the two most common advance directives are a living will and a durable power of attorney for health care (often called a health care proxy or agent). A living will describes the kinds of medical care you would or would not want in certain serious situations. Naming a proxy identifies who can make decisions for you when real life does not match the exact examples on a form.

For families, this distinction matters because emergencies are messy. Even a well-written living will cannot anticipate every detail. The proxy is the person who interprets values in context—who can ask the doctor, “If the goal is comfort, what does that look like tonight?” and who can make decisions under pressure without turning the moment into a family argument.

If you want a Funeral.com resource that walks through this gently and practically, start with Advance Directives and Living Wills: Making Medical Wishes Clear Before the End of Life, and pair it with Talking About End-of-Life Wishes with Family if the conversation part is the barrier.

DNR: A Medical Order About CPR, Not a Statement About All Care

A do-not-resuscitate order (DNR) is often misunderstood. People hear “do not resuscitate” and assume it means “do not treat” or “no care.” That is not what it means.

MedlinePlus explains that a DNR is a medical order written by a health care provider that instructs providers not to perform CPR if breathing stops or the heart stops. That’s the scope: CPR and resuscitation efforts. The National Institute on Aging also describes a DNR as becoming part of a person’s medical chart so staff know not to attempt CPR or certain life-support measures if breathing and heartbeat stop.

It is also important to understand what DNR does not do. A DNR does not automatically mean “no antibiotics,” “no oxygen,” “no pain medication,” or “no hospital.” It does not prevent comfort care. In fact, for many people, it is part of a broader comfort-focused plan. If you want a deeper clinical explanation of the common confusion, the NIH’s NCBI resource Do Not Resuscitate emphasizes that DNR does not mean all treatments are discontinued.

In the real world, a DNR is most useful when the question is specifically about resuscitation: if your heart stops, do you want CPR and advanced life support? Some people do. Some people do not. Many people decide differently depending on prognosis, frailty, and goals. What matters is that the decision is clear enough to be followed during the most time-sensitive moment.

POLST: Portable Medical Orders for Serious Illness

A POLST form (Provider Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment) is designed to translate a person’s treatment wishes into medical orders that can be followed across care settings—home, nursing facility, hospital, or hospice—especially during emergencies. The key word is “orders.” POLST is not simply a statement of preferences; it is meant to function as actionable instructions for clinicians.

The National POLST organization explains that a POLST form tells health care providers what you want during a medical emergency, including whether to attempt CPR, whether you want certain medical treatments, and whether you want transfer to a hospital. National POLST also describes POLST forms as out-of-hospital medical orders that travel with the patient so that the plan is not lost when the setting changes. You can read more on POLST: About.

Another practical point is who POLST is for. POLST is generally intended for people who are seriously ill or frail, not for every healthy adult filling out routine paperwork. CaringInfo’s explanation of POLST as portable medical orders emphasizes that POLST applies to a limited population and addresses a limited number of critical decisions. In other words, POLST is a high-importance tool for the stage of life when emergency decisions are likely and the care goals are clearer.

In a Medical Emergency, Which Document “Wins”?

Families often ask this because they are afraid a document will be ignored. The most accurate answer is that different documents guide different parts of the system.

An advance directive is essential because it names who can speak and what values should guide decisions, but it may not function as a set of immediately actionable medical orders in the field. A DNR and POLST are designed to guide emergency actions because they are medical orders. National POLST specifically frames POLST as instructions for what you want “during a medical emergency.”

That said, practical reality matters as much as theory. The document that can be followed is the document that can be found. In urgent moments, clinicians and emergency responders often act based on the information available at the point of care. This is why storage, visibility, and communication with the care team are not “extra work.” They are part of making your wishes real.

Why These Decisions Come Back to CPR Outcomes

One reason families avoid talking about DNR or POLST is that the topic feels like choosing death. In reality, the conversation is often about the likely outcomes of resuscitation and what kind of life would follow, especially for someone with serious illness or frailty.

The American Heart Association’s 2025 CPR and ECC guideline summary notes that survival to hospital discharge for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is approximately 10.5%, and survival for in-hospital adult cardiac arrest is approximately 23.6%, with variation by setting and circumstance. Those numbers are not meant to persuade anyone in a particular direction. They are meant to ground the conversation in reality: CPR is not a simple reset button, and outcomes differ dramatically depending on overall health, cause of arrest, and how quickly high-quality CPR and defibrillation occur.

A compassionate planning conversation is often less about whether CPR is “good” or “bad,” and more about alignment. If a person’s goal is to be comfortable at home and avoid invasive procedures with low chance of meaningful recovery, they may choose a DNR or POLST options that reflect that. If a person’s goal is to attempt every life-prolonging measure, their choices can reflect that too. The ethical center is not the intervention; it is whether the intervention matches the person.

How Families Decide What to Put in Writing

Most people do not decide by reading a form once. They decide by talking through real scenarios. What does quality of life mean to your loved one? What outcomes would feel acceptable, and what outcomes would feel like suffering? What tradeoffs are they willing to accept for more time? These are values questions first, medical questions second.

A helpful approach is to start with the proxy conversation. “If I can’t speak, I want you to speak for me. Here’s what matters to me.” Then move to the living will. Then, if serious illness or frailty is present, ask the clinician whether POLST is appropriate now. That sequencing tends to reduce overwhelm.

Medicare explicitly recognizes the importance of these conversations. On Medicare.gov, Medicare explains that advance care planning involves discussing and preparing for future care if you need help making decisions for yourself and that completing an advance directive can be part of that process. CMS also provides clinician-facing guidance on how advance care planning services can be offered and billed, which underscores that these conversations are not fringe—they are a legitimate part of medical care.

Make the Paperwork Usable: Storage, Sharing, and “What EMS Will Actually See”

Families often do the hard part—filling out forms—then accidentally make the plan impossible to follow by storing it where no one can find it quickly. If you want your wishes respected in real life, your plan has to be visible in real life.

That usually means your proxy has a copy, your doctor has a copy, and the document is in the medical record where possible. If a person is receiving serious-illness care at home, it also means the plan is physically accessible in the home in whatever way your care team recommends. Hospice and palliative care teams are typically very familiar with how their local systems handle POLST and DNR visibility, and they can guide you in a way that matches your state’s expectations.

If you want a Funeral.com guide that focuses on the practical “where is everything?” problem—documents, passwords, account info, and the paperwork families scramble for after a crisis—read Important Papers to Organize Before and After a Death. It’s written for real households, not idealized filing cabinets.

How This Connects to Home Hospice and Comfort-Focused Care

When a loved one is approaching end of life, these documents stop being theoretical. They become the backbone of care decisions—especially if the person hopes to remain at home. If your family is considering home hospice, it helps to understand what hospice covers, how support changes during crises, and how planning reduces ER-driven decisions. Medicare’s hospice coverage overview is here: Medicare hospice care, and Funeral.com’s companion guide Home Hospice: What It Is, What It Covers, and How to Prepare explains the real day-to-day experience for families.

If you are in hospice planning, a practical question to ask the team is: “Do we need a POLST or a DNR in addition to our advance directive, and what does it look like in this state?” That single question often turns vague fear into a concrete plan.

What These Documents Are Not: Wills, Funerals, and Memorial Preferences

It’s common to blur medical planning and after-death planning because both are emotionally connected. But they are different tools. An advance directive guides medical decisions when a person cannot speak. A will and related estate documents handle property and legal responsibilities after death. Funeral planning and memorial preferences—burial versus cremation, service tone, music, readings, and what should happen with ashes—are a different category again.

Still, families often feel relief when medical planning and memorial planning are connected gently, because it reduces uncertainty on both sides of the threshold. If you want to capture preferences in a way that helps your family later, Funeral.com’s guide Preplanning Your Own Funeral or Cremation: Benefits, Decisions, and What to Put in Writing offers a compassionate approach to documenting wishes.

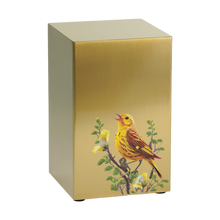

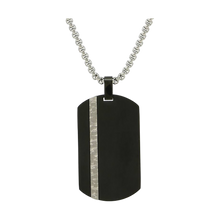

For families choosing cremation, it can also help to have a simple note about preferences for memorialization, because that’s where survivors often feel stuck: keeping ashes at home, placing an urn in a cemetery, sharing among relatives, or choosing something wearable. If that’s part of your plan, Funeral.com’s collections for cremation urns for ashes, keepsake urns, and cremation jewelry can help families see options calmly—without forcing anyone to decide everything immediately.

A Calm Closing Thought

Planning does not remove grief. What it removes is the added suffering of guessing. An advance directive gives your family a compass. A DNR clarifies what should happen if your heart or breathing stops. A POLST translates your goals into portable medical orders that can guide emergency care when serious illness makes those moments more likely.

If you’re unsure where to begin, start with the conversation and the proxy. Then complete your state-appropriate forms. Then make them findable. When families do those three things, they rarely feel “perfectly prepared,” but they do feel less afraid—and that is often the difference between a crisis that breaks people and a crisis that, while still painful, is navigated with dignity and love.