Most people don’t worry about being “funny” at a funeral. They worry about getting through the first sentence without shaking, about saying something true without falling apart, and about honoring the person in a way that feels recognizable. And then, somewhere in the middle of writing, a memory appears that makes you smile—a line they used to say, a habit that was so uniquely them, a moment that still makes the family laugh even now. That’s usually how humor in a eulogy shows up: not as a plan to tell jokes, but as a reminder that love didn’t disappear when grief arrived.

Used well, gentle humor can do something surprisingly tender. It can lower the tension in the room, give people permission to breathe, and let everyone remember the person as a whole human—not a highlight reel, not a saint, not just a loss. Used poorly, it can feel like a spotlight on someone else’s pain, a break in the dignity of the moment, or an uncomfortable performance when people were hoping for comfort. That’s why funny eulogy etiquette is really about judgment, pacing, and empathy. It’s not “Can you joke in a eulogy?” It’s “Can you bring light without taking anything away?”

Why a little laughter can be part of a respectful goodbye

There’s a reason so many families talk about wanting a service that “feels like them.” Funeral rituals have always held space for tears, but they also hold space for storytelling—because stories are how a life becomes tangible again, even for a few minutes. In many rooms, laughter is not the opposite of grief; it’s a brief companion to it. It’s the moment people recognize themselves in the memory you’re describing, and they realize they aren’t grieving alone.

Humor, at its best, is not a detour. It’s a form of accuracy. If the person was playful, quick-witted, gently mischievous, or known for saying the thing that made everyone relax, an entirely humorless eulogy can feel oddly incomplete. That doesn’t mean every life calls for levity, and it doesn’t mean the speaker has to “land” anything. It means you’re allowed to tell the truth about who they were.

It also helps to recognize how modern memorial planning has shifted toward personalization. In the U.S., cremation continues to rise, and with that often comes more flexibility in timing and format—services held weeks later, gatherings at nontraditional venues, and celebrations of life that lean heavily on stories and shared memories. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the U.S. cremation rate is projected at 63.4% for 2025 (with long-term projections continuing upward). According to the Cremation Association of North America, the U.S. cremation rate for 2024 is listed at 61.8%, with continued growth projected over the coming years. Those numbers don’t tell you what your eulogy should sound like, but they do reflect a broader reality: families increasingly shape memorials around personality, not a single “one-size” template.

When humor works in a eulogy

The simplest way to think about how to add humor to a memorial speech is that humor works when it serves connection. The room doesn’t need to laugh loudly. The goal is not applause. The goal is recognition: “Yes, that was them.” When that recognition lands, it tends to feel like warmth rather than comedy.

It matches the person’s public self, not just a private inside joke

There’s a difference between a family-only story and a story that will make sense to people who knew them in different contexts—coworkers, neighbors, friends from different seasons of life. Humor tends to land safely when it’s understandable without a lot of explanation. If you have to say, “You had to be there,” it may still be worth telling, but it’s usually better told as a tender anecdote rather than a punchline.

The speaker has the relationship “rights” to tell it

One of the quiet rules of eulogy do’s and don’ts is that permission is built into proximity. A spouse can often say things a coworker shouldn’t. A lifelong friend may have more room for teasing than a distant relative. If you’re not sure whether the room will grant you that permission, assume it won’t. When people feel protective, they may interpret a joke as disrespect even if you intended affection.

It stays kind, not clever

Comforting humor is usually generous. It doesn’t embarrass. It doesn’t score points. It doesn’t put someone else on the spot. It’s the kind of detail that makes people smile because it’s gentle, and because it carries love inside it. If you have to “win” the line, it’s probably not the right line for a memorial service speech.

When humor doesn’t work, and why it can backfire

Families often ask some version of can you joke in a eulogy because they’re aware of the risk. The risk is rarely that someone won’t laugh. The risk is that someone will feel exposed, minimized, or blindsided. There are a few common situations where humor is more likely to hurt than help.

When grief is raw and the room is still in shock

If the death was sudden, traumatic, or recent, people may not have emotional bandwidth for levity. They’re still orienting to the reality that it happened. In that context, humor can feel jarring—like someone changed the subject too quickly. That doesn’t mean you must avoid all warmth, but it often means you keep any light moment small and grounded, and you return to sincerity quickly.

When the story relies on conflict, addiction, infidelity, money, or family fracture

Even if the person used humor to cope, a eulogy is not the place to be “honest” in a way that reopens wounds. If the joke requires you to reference a painful topic, it’s usually not safe. A good rule is that you should never make the most vulnerable person in the room feel like the target, even indirectly.

When the humor would be funny only if the person were alive to deliver it

Some people were hilarious because of timing, facial expressions, or a kind of teasing that only worked because everyone knew their heart. When someone else repeats it, it can sound harsh. If you find yourself thinking, “This was funny when they said it,” pause and ask whether it will still feel loving when someone else says it at their funeral.

A practical way to “read the audience” before you decide

Most speakers don’t have the luxury of perfect certainty. You may be writing in a haze. You may not know everyone attending. You may be trying to respect religious traditions, family preferences, and your own grief at the same time. If you need a calm way to evaluate whether humor belongs, use this simple framework: consent, clarity, and compassion.

- Consent: Would the closest family members feel respected by this story, and have you checked with them if you’re unsure?

- Clarity: Will most people in the room understand the point without needing extra context?

- Compassion: Does the humor lift people up, or does it risk making someone feel small, exposed, or “on display”?

If your story fails any one of those, it doesn’t mean you have to discard it forever. It may simply belong at the reception, in a private family gathering, or in a note placed with personal keepsakes. The goal is not to censor the person’s personality; it’s to protect the people who are trying to say goodbye.

Examples of “safe” warmth that usually fits the room

When families search eulogy stories examples, they often want something they can borrow without causing harm. The safest humor usually looks like affectionate specificity—small, vivid details that are charming because they’re true. Below are examples designed to be adaptable, not copied word-for-word. You can adjust tone based on the room.

Gentle habits that made them unmistakably themselves

“If you ever called Dad and he didn’t answer, you could set a timer. He would call back exactly three minutes later, like it was a rule written somewhere. And if he didn’t call back in three minutes, it meant he was already on his way over.”

“She had a talent for turning a grocery list into a life lesson. You’d ask what she needed, and somehow you’d end up hearing a story about her grandmother, an argument for buying better tomatoes, and a reminder to call your sister.”

“Love disguised as comedy” stories

“He teased all of us, but it was never mean. It was his way of saying, ‘I’m paying attention.’ If he gave you a nickname, it meant you mattered to him.”

“My mom’s superpower was making a room less tense. She didn’t do it by avoiding hard things—she did it by reminding you, in the middle of the hard thing, that you were still a person who could breathe.”

Self-deprecating humor that keeps the spotlight off others

“I tried to write this without crying. That lasted about forty-seven seconds. So if you see me pause, it’s not because I forgot what I wanted to say. It’s because I’m trying to say it with the kind of steadiness he always had.”

“I learned quickly that you cannot ‘out-plan’ grief. I also learned you cannot out-plan this family. If you handed them a schedule, they would somehow turn it into three side conversations, a hug line, and an impromptu potluck.”

How to build a eulogy that uses humor without derailing the tone

One of the most reliable ways to keep humor safe is to place it inside a structure that already signals respect. Think of your eulogy as a bridge: you are bringing people from shock into memory, from memory into meaning, and from meaning into farewell. Humor can live on that bridge, but it shouldn’t become the whole crossing.

Open with grounding, not entertainment

Start by naming why you’re there and what the person meant. Even one sentence of steady sincerity creates a container for anything that follows. It tells the room, “We are safe. This is not a performance.” After that, a small warm detail will often land naturally.

Use humor as a doorway into a value

The most comforting “funny” moments are rarely about the laugh itself. They’re about what the detail reveals: generosity, loyalty, stubbornness that was actually devotion, the way the person loved. If you tell a story that makes people smile, take one more sentence to connect it to character. That is what keeps the tone anchored.

Return to tenderness quickly

If a moment gets a laugh, let it breathe, then guide the room back gently. You can do that with a simple transition: “And underneath that humor was…” or “What I’ll miss most is…” This keeps the eulogy from feeling like a set of bits.

Coordination matters: how to avoid surprises for the family

Many of the hard moments around memorial service speech tips come from surprise. A speaker shares a story they assumed was harmless, and someone else hears it as an exposure. If you want to use humor, the most respectful step is also the most practical: run the story by a family member who is closest to the loss. Ask, “Does this feel like him? Does this feel safe to you?”

If you’re working with a funeral director or planning team, you can also ask about the overall tone of the service. Some rooms are structured around prayer and tradition. Some are structured around music and storytelling. Your job is not to force your preferred tone into the room. Your job is to align your words with what the family is trying to create.

How humor connects to the rest of the memorial plan

A eulogy is one part of a larger goodbye. Many families find that the most comforting services are the ones where the spoken words match the other elements: photos that feel real, music that sounds like the person, and rituals that give people something to do with their hands and hearts. If your loved one is being cremated, you may also be navigating decisions about what to do with ashes, whether you’ll be keeping ashes at home, or whether a scattering or water burial ceremony is part of the plan.

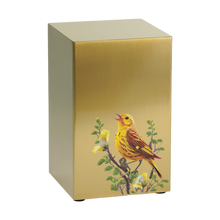

If you’re at that stage, it can help to know there’s no single “correct” next step. Some families choose a full-size urn and keep it in a dedicated space. Others choose keepsake urns so multiple relatives can hold a small portion close. Some choose small cremation urns for a more discreet home memorial. If you’re looking at options, Funeral.com’s Cremation Urns for Ashes collection is a broad starting point, while Small Cremation Urns for Ashes and Keepsake Cremation Urns for Ashes can be helpful when you’re thinking about sharing, travel, or a smaller display footprint.

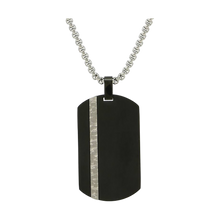

Some families want a memorial item that stays close in daily life rather than on a shelf. That’s where cremation jewelry can be meaningful, especially cremation necklaces that hold a small amount of ashes. If that resonates, you can explore Cremation Necklaces, and Funeral.com’s Journal has gentle, practical guidance on cremation necklaces for ashes and how cremation jewelry works.

If you’re grieving a companion animal, the same “personality matters” principle applies. A pet memorial can include stories that make people smile through tears, and it can include a tangible tribute that feels like your pet. Funeral.com’s Pet Cremation Urns for Ashes collection includes a wide range of styles, including Pet Figurine Cremation Urns for Ashes that look like a decorative sculpture and Pet Keepsake Cremation Urns for Ashes for sharing a small portion among family members. If you need help choosing, Funeral.com’s guide to pet urns for ashes can make the next step feel less overwhelming.

And if you’re juggling budget questions while making all of these decisions, you’re not alone. Families often ask how much does cremation cost because they’re trying to stabilize the practical side of loss. Funeral.com’s cremation costs breakdown is a useful companion when you want to understand what you’re being quoted and why.

All of this connects back to your eulogy more than you might expect. When a service is personal—when it uses the person’s real words, real habits, real humor—families often feel more confident about the choices that come next. The memorial becomes coherent. It sounds like them. It looks like them. It holds them in a way that feels steady.

FAQs about humor in a eulogy

-

Can you joke in a eulogy if the person loved comedy?

Yes, but aim for affectionate humor rather than “jokes.” The safest approach is to share a story that naturally contains a smile, then connect it to a value—kindness, loyalty, curiosity, humor as comfort—so the tone stays grounded. If you’re unsure, ask a close family member what would feel respectful in the room.

-

What are the biggest “don’ts” for humor in a memorial service speech?

Avoid anything that could embarrass the family, expose private details, or rely on conflict. Steer clear of humor about addiction, money, infidelity, unresolved family fractures, or “edgy” material that would split the room. If the laugh requires someone else to feel small, it isn’t safe for a eulogy.

-

How do I know whether the audience will accept humor?

Use three checks: consent, clarity, and compassion. Consent means the closest family members would feel respected by the story. Clarity means most people will understand it without a long explanation. Compassion means the humor lifts people up instead of making someone feel exposed. If any check fails, keep the moment warm but not “funny.”

-

Can I include funny eulogy stories if children are present?

You can, but keep it simple, kind, and clean. Children tend to read tone more than nuance, so gentle humor about habits, favorite sayings, or sweet quirks is usually safer than irony or sarcasm. If the story needs adult context, it may belong at a reception or private gathering instead.

-

What if I start a humorous story and it doesn’t land?

Don’t chase the laugh. Pause, smile gently, and transition to meaning: “What I loved about that was…” or “That was so like them because…” People will follow your lead. A eulogy doesn’t need punchlines—it needs truth, warmth, and steadiness.

A closing thought: warmth is more important than wit

If you’re writing a eulogy and wondering whether humor belongs, it may help to reframe the goal. You are not trying to be funny. You are trying to be faithful—to the person, to the family, and to the room. If a light moment helps people feel the person’s presence again, it can be a gift. If it risks making anyone feel unprotected, it isn’t worth it.

In the end, the safest humor is rarely the clever line. It’s the loving detail that makes people whisper, “That’s exactly them.” And when that happens, even for a second, grief and gratitude can sit in the same chair. That’s not a detour from mourning. That’s part of what remembrance is.