You can feel it before you even decide to do it—the pull toward a name carved in stone. Maybe you’re walking a cemetery for the first time since the funeral. Maybe you’re tracing family history and you finally found the marker you’ve been looking for. Or maybe you’re standing in front of an older stone that carries details you didn’t expect: a carved lamb, a clasped hand, an anchor, an entire life hinted at in a few quiet symbols.

That’s where grave rubbings etiquette becomes more than a hobby question. A rubbing can preserve names and designs, but it can also harm fragile markers if it’s done on the wrong stone—or done with the wrong materials. In many historic cemeteries, “good intentions” are exactly what leads to damage: pressure on weathered surfaces, wax or pigment residue that’s hard to remove, or small chips that become bigger problems over time. The most respectful approach is to slow down, understand the risks, and choose the method that protects the memorial for everyone who will come after you.

Why grave rubbings feel meaningful—and why caution matters

Grave rubbings sit at the intersection of art, memory, and documentation. They can be a way to bring home the carved lettering of a loved one’s marker, or to record a design that might not photograph well in flat light. They can also be a way of learning—of noticing what you would otherwise miss.

But preservation professionals have become increasingly clear about the risk side of the equation. A National Park Service cemetery etiquette guide warns that gravestone rubbing can damage markers, and advises checking with the cemetery’s managing group first or choosing a safer method. When the people tasked with protecting burial grounds emphasize “ask before you touch,” it’s worth listening—especially if you’re working around older or softer stone.

Many preservation guides go even further: they discourage rubbings in historic cemeteries because damage can be permanent. The Michigan Historic Cemeteries Preservation Guide includes a section bluntly titled “Gravestone Rubbing – Don’t,” describing common ways rubbings can harm inscriptions and the stone’s surface over time. That doesn’t mean every rubbing is automatically wrong everywhere. It means you should treat rubbing as a special-case technique—not a default—and you should assume that older stones deserve a lighter, less invasive approach.

Permission first: the most important step in cemetery rubbings

If you take only one practical point from this guide, let it be this: cemetery permission rubbing is not optional. It’s the foundation of respect and the quickest way to avoid a situation where you unintentionally violate cemetery policies.

Start with the place itself. Many cemeteries have posted rules at the entrance or on their website. If you see “no rubbings,” believe it and stop there. If there’s an office, staff member, sexton, caretaker, or church administrator, ask directly. In a municipal cemetery, that might be the superintendent. In a historic burying ground, it might be a historical society or a “friends of the cemetery” group. When rubbings are allowed, some cemeteries require a permit or ask you to sign in—often because they’re trying to protect fragile markers or track activity during preservation work.

Permission is also about people, not just policies. Even in public cemeteries, families visit to grieve, not to watch a project unfold on the stone next to them. Good grave rubbings etiquette means choosing a quiet time, staying within your space, and leaving no trace—no tape residue, no litter, no shifted flowers, no disturbed decorations.

If you’re visiting a military or national cemetery, it’s especially important to understand the culture of the space. The expectations often center on quiet, minimal disruption, and respectful photography. If you’re unsure what’s appropriate, Funeral.com’s guide on visiting a national cemetery is a helpful companion for understanding how to honor the setting while still documenting what matters to your family history.

How to decide whether a stone is too fragile for rubbing

The hardest part of rubbing safely is that deterioration is not always obvious until it’s too late. A stone can look “fine” from a few feet away and still have a surface that is sugaring, flaking, or separating in thin layers. This is where rubbing fragile stones risks becomes very real: the action that creates the rubbing—repeated friction and pressure—is exactly what fragile surfaces can’t tolerate.

In historic headstone preservation work, one of the most consistent principles is “do no harm.” The National Park Service has used that phrase explicitly in guidance about cemetery conservation and cleaning practices, emphasizing that rough treatment can accelerate deterioration and that long-term impacts matter as much as short-term appearance. While that article focuses on cleaning, the underlying logic is the same: when a stone is already vulnerable, added friction is not neutral.

As a practical, family-friendly rule: if the inscription is deeply worn, the surface is powdery, the marker is cracked, the stone wobbles, or flakes are already lifting, do not rub. If you tap the stone gently and it sounds hollow, or you notice separation and flaking along the face, consider that a stop sign. Many preservation guides describe these conditions as reasons to avoid rubbing because “any pressure or friction” can cause serious damage.

If you want a clearer sense of how stones age—and what “normal weathering” versus “dangerous fragility” looks like—Funeral.com’s cemetery care resources can help you slow down and assess. Start with Caring for a Marker: Simple Maintenance Guidance and, if you’re dealing with granite, the more material-specific how to clean and care for a granite headstone without causing damage article. Even if you never clean a stone yourself, learning what “unsafe contact” looks like will make you a better caretaker in the moment.

How to do a grave rubbing safely when it is allowed and appropriate

There are situations where a rubbing is permitted and the stone is sound enough to handle it—typically newer markers, durable materials, and clear cemetery approval. In those cases, how to do a grave rubbing is less about getting a perfect image and more about controlling pressure, controlling materials, and protecting the stone’s surface from residue.

Think of this as a gravestone art technique with a conservation mindset. Your goal is to make the rubbing with the lightest contact possible, for the shortest amount of time possible, without leaving anything behind.

If you are cleared to proceed, a simple kit is usually enough. The key is choosing safe materials for grave rubbings that are designed for gentle contact and that minimize the risk of bleed-through or residue:

- Paper large enough to cover more than the area you plan to rub (so pigment stays on the paper, not the stone)

- Low-tack masking tape (never duct tape, strong adhesives, or anything that can leave residue)

- Rubbing wax designed for paper (avoid permanent markers and anything that could bleed through)

- Scissors for trimming paper to a manageable size

- A soft brush and plain water only for removing loose dust (skip detergents, bleach, vinegar, and “home remedies”)

The technique itself should feel almost anticlimactic. Secure the paper so it doesn’t shift. Use broad, light strokes at first—just enough for the relief to show. If you find yourself pressing harder to “force” detail, stop. That pressure is often what damages edges and weakens already-weathered carving. If the paper tears, stop immediately; a torn sheet increases the chance that wax or pigment contacts the stone, and removing residue can require aggressive methods that create additional harm.

Just as important: avoid the temptation to “improve readability” with substances applied to the marker. The Association for Gravestone Studies discourages methods like flour and shaving cream because residue can remain in the stone and contribute to deterioration. If you’re trying to read a worn inscription, it’s usually safer to change the light or your camera settings than to apply anything to the marker.

Alternatives to grave rubbings that preservation groups prefer

When the stone is historic, fragile, or you simply want the safest option, an alternative to grave rubbings is often the better answer. The good news is that modern tools make non-invasive recording easier than it used to be.

Start with photography, but photograph like someone who’s trying to “read” the stone, not just capture it. Side lighting (early morning or late afternoon) often reveals relief that overhead sun hides. A flashlight held at a low angle can help in shaded areas. The Association for Gravestone Studies also recommends using a mirror to direct bright sunlight across the face of the stone to cast shadows in the lettering, and using photo editing tools like “invert colors” to make inscriptions stand out in a digital image.

If you want to go further, some families use digital scanning or photogrammetry apps to create a 3D record without rubbing the surface. The right approach depends on the cemetery’s rules and the marker’s condition, but the principle is consistent: preserve details without friction, without residue, and without risking the edges of carved letters.

And sometimes the most respectful alternative is simply documentation plus patience: take multiple photos, write down the inscription, note the location, and check whether local historical societies have transcriptions or surveys. Preservation often works best when many small records add up, rather than when one “perfect” record risks damage.

When a life isn’t marked by a headstone: connecting cemetery heritage with cremation choices

It may seem like grave rubbings and cremation planning belong in separate conversations, but many families experience them side-by-side. You might be visiting ancestral graves while also planning a modern memorial that won’t involve a traditional marker. Or you may be feeling the weight of cemetery history while making choices about an urn, a keepsake, or a scattering ceremony.

Cremation is now the majority disposition in the United States, which means more families are making decisions about memorialization outside a cemetery setting. According to the Cremation Association of North America (CANA), the U.S. cremation rate was 61.8% in 2024 and is projected to rise further. The National Funeral Directors Association reports a projected U.S. cremation rate of 63.4% in 2025 and notes that cremation is expected to continue increasing in the decades ahead. These shifts matter because they change the practical question many families ask next: not only “Where is the grave?” but also “How do we keep the person close?”

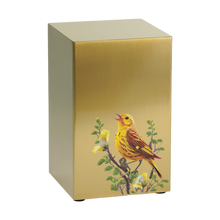

For some families, the answer is a home memorial anchored by cremation urns for ashes. If you’re exploring styles, materials, or personalization without rushing yourself, Funeral.com’s cremation urns collection is a broad place to start, and the Journal guide How to Choose the Right Urn explains capacity, placement, and budgeting in plain language.

Other families choose a “shared” approach—one primary urn, plus smaller pieces for the people who need something tangible. That is where small cremation urns and keepsake urns can be a practical kindness, not an extra complication. If you want a deeper, gentle walkthrough of how these decisions fit together, Funeral.com’s Journal article funeral planning guidance for cremation choices is written for families trying to make a plan they can live with.

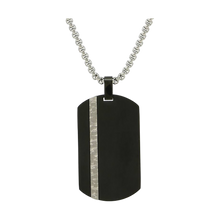

For daily closeness, many people prefer cremation jewelry. A small, wearable portion can be a comfort on ordinary days that suddenly feel unfamiliar. If you’re comparing styles, you can explore Funeral.com’s cremation jewelry collection or focus specifically on cremation necklaces, then read Cremation Jewelry 101 for practical tips and expectations.

Pet loss belongs in this conversation too. A companion’s urn can be as meaningful as any family memorial, especially when the relationship was daily and deeply bonded. Funeral.com’s pet urns collection includes a wide range of pet urns for ashes, including designs meant for dogs, cats, and other companions. If you’re drawn to a memorial that reflects your pet’s presence in a more visual way, you may find comfort in pet figurine cremation urns. And if you’re sharing a portion among family members, pet keepsake cremation urns are designed for that exact need.

Finally, many families wrestle with practical questions that carry emotional weight: keeping ashes at home, scattering, or planning a ceremony later when travel and schedules allow. Funeral.com’s guide to keeping ashes at home addresses safety, respect, and day-to-day handling. If your family is considering water burial, the Journal article on water burial and burial at sea explains the terminology and planning details. And if you’re still at the earliest stage—staring at the question and not sure where to begin—what to do with ashes offers practical ideas without pushing you into a decision before you’re ready.

Cost questions often sit underneath everything, even when families feel awkward saying so out loud. If you’re searching how much does cremation cost, you’re not being “too practical.” You’re trying to plan responsibly. Funeral.com’s guide on how much does cremation cost breaks down common fees and variables so you can compare options with less stress.

Frequently asked questions

-

Are grave rubbings allowed in most cemeteries?

Policies vary widely. Some cemeteries allow rubbings with permission, while others prohibit them because of the damage that friction and pressure can cause to historic stones. The safest approach is to ask the cemetery office, caretaker, or managing organization before you begin, and to choose photography or another non-invasive method if rubbings are restricted.

-

What are the biggest risks of rubbing fragile stones?

The most common risks include chipping or flaking of already-weathered surfaces, abrasion along the edges of carved letters, and residue transfer if paper tears or if pigment bleeds through. Preservation guides note that this damage can accelerate deterioration over time, especially on older stones or stones that are cracked, hollow-sounding, sugaring, or unstable.

-

If a cemetery allows it, what materials are considered safer for a grave rubbing?

Use paper that covers more than the area you plan to rub, low-tack masking tape, and rubbing wax meant for use on paper. Avoid strong adhesives, permanent markers, and any method that applies substances directly to the stone. If you need to remove loose dust, use only plain water and a soft brush—skip detergents and chemical cleaners.

-

What is the best alternative to grave rubbings for older stones?

Photography with side lighting is often the safest and most effective option. Many researchers also use a mirror to cast angled sunlight across the inscription, then edit the photo (including “invert colors”) to bring out lettering. For highly significant stones, consider non-contact digital documentation methods or check whether local historical groups have existing surveys and transcriptions.

-

If there isn’t a headstone because of cremation, what are common ways families memorialize?

Many families create a home memorial with a cremation urn, share portions using keepsake urns, or choose cremation jewelry for daily closeness. Others plan a scattering ceremony later, including water burial or burial at sea when appropriate. The “right” option is the one that fits your family’s values, timeline, and comfort—especially if you’re still in the early stages of planning.