If you are walking into a funeral with an estranged relative on the guest list, you are not imagining the tension. A service that is supposed to be about honoring one life can start to feel like an emotional minefield, especially when old patterns show up in a room full of grief, extended family, and social expectations. The hard part is that you usually cannot “solve” estrangement in the days before a funeral. What you can do is reduce the opportunities for conflict, protect the most vulnerable people in the room, and keep the service respectful.

This is the quiet goal of good funeral planning when relationships are complicated: you are not trying to control anyone’s feelings. You are building a structure that makes it easier for everyone to behave. Seating, arrival timing, and clear boundaries are not cold or dramatic. They are practical kindness—especially when you are exhausted.

If you want a starting point that feels grounding, begin here: decide what would honor the person who died, and let that be the north star for everything else. Once you have that, the rest becomes less personal and more logistical, which is exactly what you need on a day like this.

Start With One Decision: What Would Honor Them Today?

Estrangement often creates a tug-of-war over symbolism. Someone may insist they “should” sit in the front row because of a title (spouse, sibling, parent). Someone else may feel that closeness is earned, not inherited. In the middle is the person who died—who cannot speak now, and who deserves a service that is not turned into a referendum on family history.

It can help to name the purpose of the day out loud, at least within the small circle of people who are coordinating details. A simple sentence like, “Our job is to keep this respectful and focused on them,” changes the tone. It also gives you a reason to say no later without turning the conversation into an argument about the past. When you are dealing with family drama at a funeral, clarity is often more effective than emotion.

If you are coordinating the service, you can also decide what kind of “contact level” you are willing to have. Some families aim for polite distance. Others choose no direct interaction at all. Either can be appropriate. The key is consistency, because inconsistency is where conflict slips in.

A Practical Seating Plan When Relationships Are Complicated

Seating is one of the most visible parts of a funeral, which is why it can trigger so much anxiety. The good news is that most funeral homes and venues handle seating flexibility all the time. Etiquette is not a law. It is a tool for reducing uncertainty.

If you want a clear baseline for who sits where at a funeral, start with Funeral.com’s guide on funeral seating etiquette for immediate family. The simplest mental map is “closest relationship sits closest to the front and the center aisle,” but families adapt for blended households, caregiving roles, and accessibility needs. In estrangement, adaptation is not a breach of tradition—it is how you prevent a confrontation in the front row.

Here are the seating principles that reduce conflict without making a spectacle of it.

- Reserve the first row (or first two) for the people who were closest in day-to-day life, not just by title.

- Create a buffer row behind or beside them for supportive relatives or close friends who can act as social “shock absorbers.”

- Avoid placing estranged parties directly next to each other, even if that means expanding “immediate family” seating sideways instead of stacking it tightly in the center.

- If a conflict is likely, ask the funeral director or staff to guide people discreetly rather than leaving it to whoever arrives first.

For many families, the most stressful moment is not the service itself, but the doorway—where people are deciding where to sit while everyone watches. Funeral.com’s article on family line-up at a funeral is helpful because it frames the day as a sequence: arrival timing, procession order, reserved rows. When you think in sequence, you can plan for the tight spots.

Buffer Strategies That Actually Work

“Buffering” is not about excluding anyone. It is about preventing a direct line of contact that can escalate quickly. A buffer can be a person (a calm cousin, a family friend), a physical layout (an aisle, a reserved row), or a timing choice (arriving early or late).

One of the most effective buffers is assigning a practical coordinator. Funeral.com’s guidance on immediate family responsibilities highlights that it is appropriate to appoint a point person to answer questions and manage logistics when you are depleted. See Funeral etiquette for immediate family: seating, duties, and what to do for language that normalizes this choice. The point person is not there to “police” emotions. They are there to keep decisions from landing on the person who is most grief-stricken.

If there is one practical rule worth repeating, it is this: do not let estranged dynamics decide the front row. Let the front row be a place of care, not conflict.

Boundaries Without a Scene

Boundaries are often misunderstood as harshness. In reality, boundaries are how you keep a day from spinning out when people are emotional. They also protect the mourners who are least able to defend themselves—an elderly parent, a grieving spouse, children who do not understand the history.

In estrangement, people sometimes arrive looking for a reckoning. The service is not the place for it. You can set that expectation ahead of time in plain, non-accusatory language. If you need scripts that do not inflame the situation, Funeral.com’s guide on boundary scripts for family requests you can’t meet offers a useful structure: acknowledge, limit, offer an alternative, and repeat. The key is to keep your sentences short. Long explanations invite debate.

Boundaries can sound like this:

- “I’m keeping today focused on them. If you want to talk about anything else, it won’t be today.”

- “We’re not changing seating at the door. Staff will help you find a place.”

- “I’m not discussing the estate here.”

If you are thinking, “This feels rigid,” remember what the boundary is doing: it is making it easier to behave. Most people can follow simple rules when the rules are clear.

How a Point Person Reduces Conflict

A point person can be a sibling with steadier nerves, a cousin who is respected by both sides, or a close friend who has no stake in family politics. Their job is to intercept friction so the closest mourners can stay present. In families dealing with funeral planning conflict, this role can be the difference between a peaceful service and a memory that feels ruined.

In practice, a point person can:

- Coordinate arrivals so estranged relatives are not forced into small talk in the parking lot.

- Confirm seating quietly with staff, especially when there is a funeral seating chart conflict.

- Redirect inappropriate conversations (“This isn’t the time—let’s focus on the service”).

- Handle practical questions from guests so immediate family is not pulled into logistics.

Notice what is missing: they are not negotiating old wounds. They are managing the environment.

Defusing the “Hot Topics” Before They Ignite

Estrangement has a way of turning practical decisions into symbolic battles. Funerals bring a cluster of decisions that can trigger conflict: who speaks, whether there is a viewing, what religious language is used, and—very often—what happens after the service. Increasingly, that includes cremation and the choices that come with it.

Cremation is now the majority choice in the United States, which means more families face decisions about remains, urns, and keepsakes. According to the National Funeral Directors Association, the U.S. cremation rate is projected at 63.4% for 2025. According to CANA (the Cremation Association of North America), the U.S. cremation rate was 61.8% in 2024. When cremation is common, disagreements about “what to do next” become common too.

This is where you want to separate two questions that people often blur together: (1) who has legal authority to make decisions, and (2) what feels emotionally fair. If your family is estranged, you do not want to discover at the worst moment that you are arguing about authority in public.

If you are worried about conflict over disposition decisions, it can help to understand that many states allow a person to assign an agent to control disposition, precisely to reduce disputes. The Funeral Consumers Alliance provides a state-by-state overview of these “designated agent” laws. You do not need to become a legal expert to benefit from this idea: when one person has clear authority, fewer decisions become group negotiations.

When Cremation Is Part of the Plan: Urns, Keepsakes, and Boundaries Around Ashes

Even when everyone agrees on cremation, families can still disagree about what happens to the ashes. In estrangement, those disagreements can become proxy battles about belonging: who gets to keep them, who gets a keepsake, whether the ashes are divided, and what “respect” looks like. This is one area where structure is your friend.

One gentle way to reduce pressure is to start with a “for now” plan. Many families keep ashes safely at home for a period of time, then decide later about scattering, burial, or dividing. Funeral.com’s guide to keeping ashes at home can help you think through safe placement and household comfort—especially if not everyone feels the same emotionally about having remains in the home. The point is not to rush a permanent decision while grief is sharp and relationships are tense.

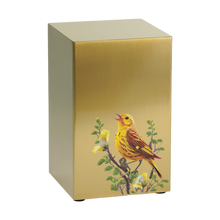

When you are choosing a primary urn, it can help to match the urn to the plan—where it will live, who will handle it, and whether it needs extra security. Funeral.com’s guide on how to choose a cremation urn walks through materials, placement, and practical tradeoffs. If you are browsing options, start with cremation urns for ashes, then narrow based on your plan. Families who want something compact (or a second container as part of a “share” plan) often look at small cremation urns for ashes, while families who want multiple small containers for shared remembrance often choose keepsake urns.

If you are anticipating conflict, naming the plan can be as important as choosing the object. A sentence like, “The primary urn will stay with the person who has legal authority, and we will revisit keepsakes later,” is not cruel. It is stabilizing. And when you do choose keepsakes, you can keep the tone gentle and non-competitive by framing them as shared remembrance rather than “ownership.” Funeral.com’s explainer on what keepsake urns are and when families choose them can help you set expectations about size and purpose.

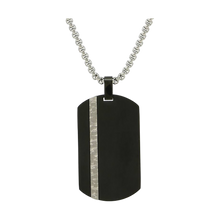

Sometimes a keepsake is not an urn at all. Some families prefer cremation jewelry—a private way to carry a small portion close without making the home feel like a memorial museum. If that is part of your family’s plan, it helps to talk about it early, before someone interprets jewelry as “taking” more than their share. Funeral.com’s Cremation Jewelry 101 is a practical guide to materials and filling, and the cremation necklaces collection is a straightforward place to compare styles. Using clear language—cremation necklaces are for a very small portion—can lower suspicion in families where trust is already thin.

If “later” includes scattering or a water burial, clarify what you mean, because families use the phrase in different ways. Funeral.com’s guide to water burial and burial at sea explains the practical difference between scattering on the surface and using a biodegradable urn that dissolves. If the ocean is involved, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency explains that cremated remains must be placed at least three nautical miles from land. In estrangement, specifics matter. Vague plans create openings for disputes.

If cost is part of the conflict (and often it is), talking about numbers can feel blunt, but ambiguity can fuel resentment. The NFDA reports a 2023 national median cost of $6,280 for a funeral with cremation (with viewing and service), which is one reason families weigh simpler options. See NFDA’s statistics page from the National Funeral Directors Association for the median cost context. For families trying to understand what they are actually paying for, Funeral.com’s guide to how much does cremation cost can help you compare what is included rather than comparing headline prices alone.

Finally, if the conflict is really about meaning—what feels respectful—sometimes the most helpful question is the simplest one: what would they have wanted? Funeral.com’s resource on what to do with ashes can be a helpful “menu” of options that keeps the conversation practical instead of personal.

What If Pets Are Part of the Story?

This may not apply to every family, but it comes up more than people expect. Sometimes the person who died was deeply bonded to a pet, and the family wants to include that relationship in the memorial. Sometimes a pet has died close in time, and grief is layered. If your family is already tense, be mindful that “small” memorial items can still become emotional flashpoints.

If your family is choosing memorial items for a pet, the same principles apply: clarify authority, choose a “for now” plan if needed, and avoid decisions at the doorway. Funeral.com’s collections for pet urns for ashes, pet figurine cremation urns, and pet keepsake cremation urns can help families compare styles and sizes without turning it into a debate about who “deserves” what. The goal is still remembrance, not competition.

Arrival, Greeting, and the Reception: The Moments That Matter Most

In estranged families, the service itself is often calmer than the transitions. People can sit quietly for a reading, a song, a prayer. The conflicts tend to happen in the margins: arrivals, greetings, the walk to the car, the reception line, the meal afterward. If you want to prevent a blow-up, design the margins as intentionally as the service.

Arrival timing is one of the simplest tools. If you are close family and you want distance, arrive early, settle, and let staff guide late arrivals. If you expect an estranged relative to arrive early and “claim” space, you can ask staff to hold reserved rows. Funeral.com’s guidance on arrival timing and seating order can help you plan this without feeling dramatic.

Greeting choices matter too. You do not owe anyone a conversation. A nod, a simple “thank you for coming,” or no interaction at all can be appropriate, depending on your safety and emotional capacity. This is where a point person can help, because they can do polite buffering while you stay focused on the person you are there to honor.

If there is a reception after the service, consider whether a receiving line helps or hurts. In families with tension, a line can force interaction and create pressure. Some families choose to skip it entirely, or keep it very short. It can also help to seat people at separate tables, or to create smaller clusters so no one is trapped in a conversation they cannot exit gracefully.

When to Ask for Help

You do not have to manage this alone. Funeral directors, clergy, celebrants, and venue staff have seen difficult family dynamics before, and they can often help in discreet ways—holding reserved rows, guiding flow, and protecting the front of the room from last-minute disputes. If you are worried about a specific person causing disruption, you can also ask what safety measures exist at the venue. This is not about “punishing” anyone. It is about making the environment predictable enough for grief to exist without fear.

If there is a history of threats or violence, prioritize safety and speak to the venue in advance. Emotional discomfort is hard, but physical safety is non-negotiable.

A Gentle Reminder: You Don’t Have to Fix the Relationship Today

Estrangement can make you feel like every shared event is a test. Funerals can intensify that feeling because the room is filled with family roles and public expectations. But a funeral is not a courtroom and it is not group therapy. It is a day of remembrance.

If you do nothing else, do this: choose the structure that protects the closest mourners, reduces uncertainty, and keeps the service centered on the person who died. That is not avoidance. It is respect.

FAQs

-

Who sits where at a funeral when the family is estranged?

Start with a simple baseline—closest relationship sits closest to the front and center—then adapt to reduce conflict. Many families reserve the first row (or first two) for the people who were most involved day-to-day, then place supportive “buffer” relatives or friends nearby. Funeral.com’s guide to funeral seating etiquette for immediate family can help you build a plan that is respectful and flexible: funeral seating etiquette for immediate family.

-

How do I set boundaries at a funeral without causing a scene?

Keep boundaries short, consistent, and focused on the purpose of the day. Avoid long explanations. You can use a simple structure—acknowledge, limit, offer an alternative, repeat—so your words stay calm even if someone pushes. Funeral.com’s boundary scripts are designed for exactly this moment: how to handle family requests you can’t meet.

-

What if relatives disagree about what to do with ashes?

Separate legal authority from emotional fairness. If your family is already strained, a “for now” plan can reduce pressure: keep ashes safe, then decide later about sharing, scattering, or keepsakes. Funeral.com’s resources on keeping ashes at home and what to do with ashes can help you outline options without rushing: keeping ashes at home and what to do with ashes. If you want to understand how designated-agent laws can reduce disputes, the Funeral Consumers Alliance offers a state-by-state overview: state-by-state assigning an agent to control disposition.

-

Is cremation common enough that we should plan for urn and keepsake decisions?

Yes. Cremation is now a majority choice, which means urn, keepsake, and ashes decisions are increasingly common. The National Funeral Directors Association reports a projected U.S. cremation rate of 63.4% for 2025: National Funeral Directors Association. CANA reports a U.S. cremation rate of 61.8% in 2024: CANA industry statistics. If you are browsing options, start with cremation urns for ashes, and consider whether keepsake urns or cremation necklaces fit your family’s comfort level.

-

If we plan a water burial, what rules matter most?

Clarify whether you mean scattering on the water’s surface or using a biodegradable urn that dissolves. If the ocean is involved, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency states cremated remains must be placed at least three nautical miles from land: EPA burial at sea. Funeral.com’s guide explains what “3 nautical miles” means in real planning terms: water burial and burial at sea.